Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 59:20 — 81.5MB)

Today we shine a spotlight on Louisiana Grass Roots, a compelling new documentary produced by Dr. Phyllis Baudoin Griffard and directed by Jillian Godshall. This film captures the voices of everyday Louisianians working to preserve our state’s environmental and cultural heritage, highlighting powerful grassroots movements shaping our future.

Jillian and Phyllis join us to share the inspiration behind the documentary, the stories that moved them most, and why community-driven action matters now more than ever.

This episode is also special on a personal note—Jan Swift’s daughter, Kelly, who works in the film industry at the Manship Theater, made this introduction. Even though we all live and work in the same region, this documentary brought us together in a way that highlights what community truly means in South Louisiana.

About the Filmmakers – In Their Own Words

Director Jillian Godshall began by expressing gratitude for the local connection that made this collaboration possible.

“I am a filmmaker. I’m also an educator. I’ve been doing both for over 15 years at this point. It’s taken me all over the world. I’m really glad to be here in Lafayette doing that work as well.”

Her background is deeply rooted in documentary storytelling: “My background in filmmaking is mostly in documentary filmmaking. I’ve worked on big budget, large scale reality TV show stuff—don’t tell anyone—and all the way down to where I feel most comfortable now, which is working on smaller-scale independent projects, having more of the creative leadership role, directing and being super involved in every aspect of production.”

Jillian also teaches video editing to incarcerated students through an organization called The Last Mile: “I currently teach video editing to incarcerated students… and work with Phyllis, hang out with Phyllis, plant plants with Phyllis.”

Producer Dr. Phyllis Baudoin Griffard shared her deep Louisiana roots and her global experience in science education: “I’m from Lafayette originally, grew up all over the South… I got a degree from USL in zoology and then went off to graduate school in biochemistry. I came back to Louisiana and started teaching at Xavier University, and I knew then that’s what I wanted to do.”

Phyllis’ work has always focused on connecting people to the land and ecology around them:

“Even as a biologist and teaching university students, I always was looking for local examples and to reconnect students outside the textbook to the biology that’s in their own backyard.”

She emphasized the importance of place in identity: “When I came home, I heard French, I heard the music—you can really connect to this place.”

The Origin of Louisiana Grass Roots: A Story Rooted in Place, Memory, and Rediscovery

Jillian and Phyllis did not come together through a traditional film industry channel; they were united through a local experience that awakened something deeper. Phyllis explains that after returning to Lafayette and connecting with the Acadiana Master Naturalist Program, she began to understand the importance of the Cajun Prairie through firsthand fieldwork.

“One of the topics is about the Cajun prairie… I had learned about the prairie, and I knew about it more from when we lived in Texas, because the people in and around Houston just ooh and ah about the prairie scientists we have over here: Larry Allen, Charles Allen and Malcolm Vidrine, who discovered what they have since called the Cajun Prairie. 2.5 million acres. Most of Southwest Louisiana was part of this prairie, which only less than 1% exists today.”

It was during a field trip with the Master Naturalists that she crossed paths with Jillian:

“I led one of the field trips and found out that Jill was a filmmaker, and I happened to say, ‘Oh, I just finished doing a film, The Quiet Cajuns, with Conni Castille.’ And her ears perked up and she said, ‘Well, I think we should make a film about the prairie.’”

Within two days, Jillian reached out to move the idea forward. It wasn’t a casual suggestion—it became a movement.

Funding the Vision: Community as Catalyst

Unlike many documentaries dependent on outside institutions, Louisiana Grassroots was made possible by local belief in the story.

Jillian said: “We were filming this project for over two years and had such incredible support from people along the way to make it possible. It’s one of the better-funded small projects I’ve worked on, in large part because of the support of the community, because of Phyllis’ know-how and ability to communicate these ideas to the average person.”

Phyllis detailed those early grant efforts: “The first grant we got was from the Acadiana Center for the Arts. We convinced them that we have this natural heritage around us that most of us, just because of modern life, are very disconnected from. We don’t really know what the land was like, what the people did there… and yet the reason our music and food are the way they are is because of the characteristics of the prairie and the bayous.”

She emphasized the artistic power needed to reach people:“You need powerful art to communicate big ideas. The visual.”

Additional support came from Atchafalaya National Heritage Area, Louisiana Native Plant Society, UL-Lafayette Foundation, and Cajun Prairie Habitat Preservation Society. “The Cajun Prairie Habitat Preservation Society got us to the finish line to finish production.”

Revealing a Vanishing Landscape: The Cajun Prairie as Cultural Ancestry

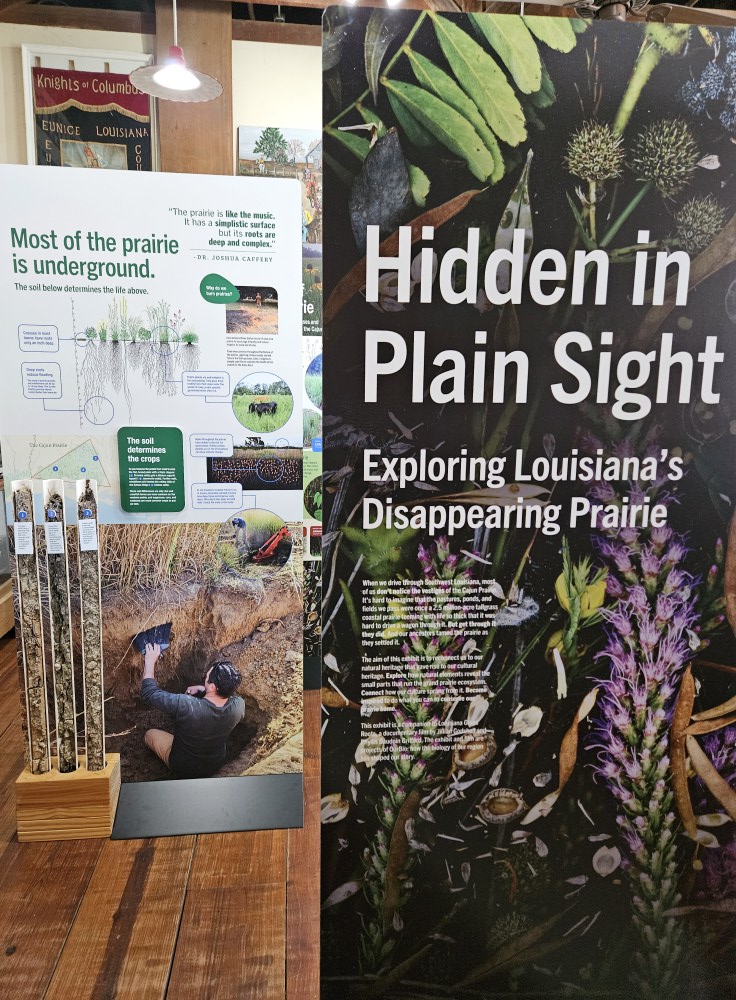

The film explores a truth many Louisianians are completely unaware of: our Cajun and Creole identity—our music, food, language, even the way our ancestors lived—is rooted in the prairie ecosystem that once covered southwest Louisiana.

Phyllis explains: “We are so proud of the music and the food that really make us who we are here. And yet the reason that they’re the way they are is because of the characteristics of the prairie and the bayous, the history of the people is the way it is because of the way the land is.”

The prairie is largely invisible now; not because it disappeared naturally, but because it was converted to agriculture due to its incredibly fertile soil.

“That’s why we’ve lost the prairies, because it was such good agricultural land.” Jillian reflected on the challenge of visually capturing something that is mostly gone: “In many ways it’s invisible to the eye… a lot of what makes the plants in the prairie so ecologically beneficial is also invisible because it’s happening under the soil.”

Jillian spent extensive time in the field not just filming, but learning: “I spent a tremendous amount of time with a camera, but more as a way to research and understand what was happening.”

Capturing What Was Lost – And What Can Be Reclaimed

One of the greatest challenges in producing Louisiana Grassroots was visualizing something that no longer exists in its original form. The Cajun Prairie, once 2.5 million acres spanning southwest Louisiana, is now less than 1% intact.

To bring this hidden world to life, the filmmakers employed creativity and collaboration.

“We were able to use animation to depict some of those invisible scientific processes, and we used a lot of archival footage to paint a picture of what the land was like and what the culture was like.”

They also incorporated footage from the 1990s documentary Wildflowers of the Cajun Prairie by filmmaker Pat Muir: “It features many of the scientists who now, 30 years later, are in our film. To be able to include his footage from the original film was really special.”

Phyllis points to these scientists, such as Dr. Malcolm Vidrine and Dr. Charles Allen, as the original visionaries: “They were really the ones who were able to communicate why it’s important, why it’s a significant part of our local cultural heritage, and they’re still doing that to this day.”

Hope Instead of Doom: Telling an Environmental Story Differently

Rather than present an environmental crisis narrative rooted in despair, Louisiana Grass Roots uplifts viewers by highlighting those actively restoring the land.

Phyllis said of Jillian: “When you see that something is disappearing, there’s that sense of doom, and Jill’s work is about environmental commitment and stewardship. How do you convey the seriousness and urgency without a sense of doom? She does that by saying, yes, these are important things, and look at the people who are doing something about it.”

Jillian affirmed the intention behind this filmmaking approach: “Filmmaking is the pinnacle of art mediums because it’s so immersive… you’re seeing and hearing and feeling and going along on a journey. It can be used for both good and bad. It’s always been really important to me to use it as a tool for positive change.”

Jillian emphasized her goal: “I don’t want to contribute to this feeling of doom and gloom… I would hope that all of us are able to appreciate the landscapes that surround us enough to want to be inspired to be involved in saving them and protecting them and celebrating them.”

Film as Education, Film as Transformation

The impact of Louisiana Grass Roots is not merely informational—it is transformational. Phyllis shared a definition that guided her vision: “The definition of learning is that the quality of your experience of the world changes. If the world doesn’t look different after you studied, then you probably haven’t really learned anything.”

That transformation begins with awareness. “When you drive down the road, you see fields or pasture and almost no one calls that prairie. But that’s what it is. My goal was that when you drive down the road, your eyes now see prairie.”

Jillian shared her personal transformation in making the film: “Making this film helped me feel really grounded here. I’ve installed a 20 by 20 little pocket prairie in my yard. My children help me take care of those plants. It’s become part of my life.”

Phyllis took it even further, restoring 30 acres of family land: “Steve Nevitt said, ‘I can tell this wants to be prairie again.’ When you become an expert in something, your world looks different.”

The Cajun Prairie is not only an ecological treasure; it shaped the culture, music, and identity of Acadiana. This documentary honors the people who carry those traditions forward.

Jillian shared how meaningful it was to include musicians and culture bearers whose artistry springs from the land itself: “We filmed with Geno Delafose and that was really special. His family members have been cattle ranchers for generations, and he is the first in his family to have been able to buy the land that he’s working cattle on. His music is in large part shaped by the land that his family has been working for generations.

The film also features Grammy-nominated musician Blake Miller of The Revelers: “He is the son of the prairie himself. It felt very special to be able to include him in the project, as well as Megan Constantin.”

Phyllis reflected on the deep connection between land, heritage, and identity in South Louisiana:

The prairie is also a story of many peoples, not just one label: “We’ve lumped everything together as Cajun, but we have Indigenous heritage, African American heritage, Creole heritage, Irish, Scottish, German — we’re a blend. Most of us are mutts. And the land shaped all of us.”

Indigenous Knowledge & The Power of Fire

One of the most powerful lessons from Louisiana Grass Roots comes from Indigenous stewardship practices, shared by Dr. Jeffrey Darensbourg: “The land, when it was being managed by Indigenous practices, was actively being managed. We think of wilderness, but they were very aware of how to manage the land in a way that was sustainable.” This includes fire — a natural and necessary part of prairie ecology. One of the big drivers of prairie health and restoration were prescribed burns. When you burn, you bring up fresh growth which brings in more bison. We grew up with Smokey the Bear, but those burns have been critical.”

The documentary reframes our understanding of “wild land,” showing that nature thrives when people work with it, not against it.

Where the Prairie Lives Today

Phyllis shares where remnants of the Cajun Prairie can still be found: “The biggest tracts are south of Lake Charles. Some are on railroad rights-of-way, because mowing and burning for maintenance accidentally mimicked natural prairie processes.” And on private family lands: “There are lots of families who have acreage. Maybe the land is no longer farmed, and they can get federal support to restore prairie ecosystems. It builds soil and has benefits for farmers.”

How the Film Was Made

Jillian described the painstaking work of capturing a lost landscape: “Lists and lists and sleepless nights… I like to have a good plan, but you need to be flexible because you’re documenting real life.”

The film took more than two years, with over 30 hours of footage edited down to 28 minutes:

“We worked with a wonderful local editor, R. J. Comeaux… he did an amazing job.” Louisina Grass Roots was filmed locally with an all local crew.

- Directed by Jillian Godshall

- Produced by Dr. Phyllis Baudoin Griffard

- Featuring Geno Delafose, Megan Constantin, Dr. Jeffery Darensbourg, Dr. Charles Allen, Dr. Malcolm Vidrine, Larry Allain, and Steve Nevitt.

- Director of Photography Rush Jagoe

- Additional Camera Drake LeBlanc and Jillian Godshall

- Drone André Daugereaux

- Sound Jillian Godshall and Rachel Nederveld

- Swing/G&E Drake LeBlanc

- Associate Producer Rachel Nederveld

- Production Assistant Maggie Russo

- Editor and Colorist RJ Comeaux

- Post Production Supervisor Allison Bohl Dehart

- Animation Camille Broussard

- Archival Footage Pat Mire

- Score Blake Miller

- Additional Music Geno Delafose

- Supported by Acadiana Center for the Arts, Cajun Prairie Habitat Preservation Society, Atchafalaya National Heritage Area, Louisiana Native Plant Society, University of Louisiana at Lafayette Foundation, Acadiana Native Plant Project

Screenings & How to Watch

The documentary has already been shown to enthusiastic audiences across Acadiana — from Vermilionville to Moncus Park — often alongside seed-collecting and restoration events:

“By the end of the year, we will have screened the film 20 times.”

Upcoming screenings include:

- NUNU Collective, Arnaudville — November 14

- Southern Screen Film Festival — Mid-November

- Crowley Forum —

The film is currently touring community screenings, with future plans to stream online and enter schools and libraries. There are also plans for curriculum pieces and educational video modules. . If you are interested in having the 30-min film screened in your area, please contact Dr. Griffard at ourlouisianabio@gmail.com. Follow the project for updates: 📷 Instagram & Facebook: Louisiana Grass Roots

Final Reflections

This documentary is not simply about plants — it is about place, identity, and stewardship.

Phyllis said it beautifully: “The definition of learning is that the quality of your experience of the world changes.” Jillian added: “I hope all of us are able to appreciate the landscapes that surround us enough to be inspired to protect them and celebrate them.”