Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 1:07:02 — 92.1MB)

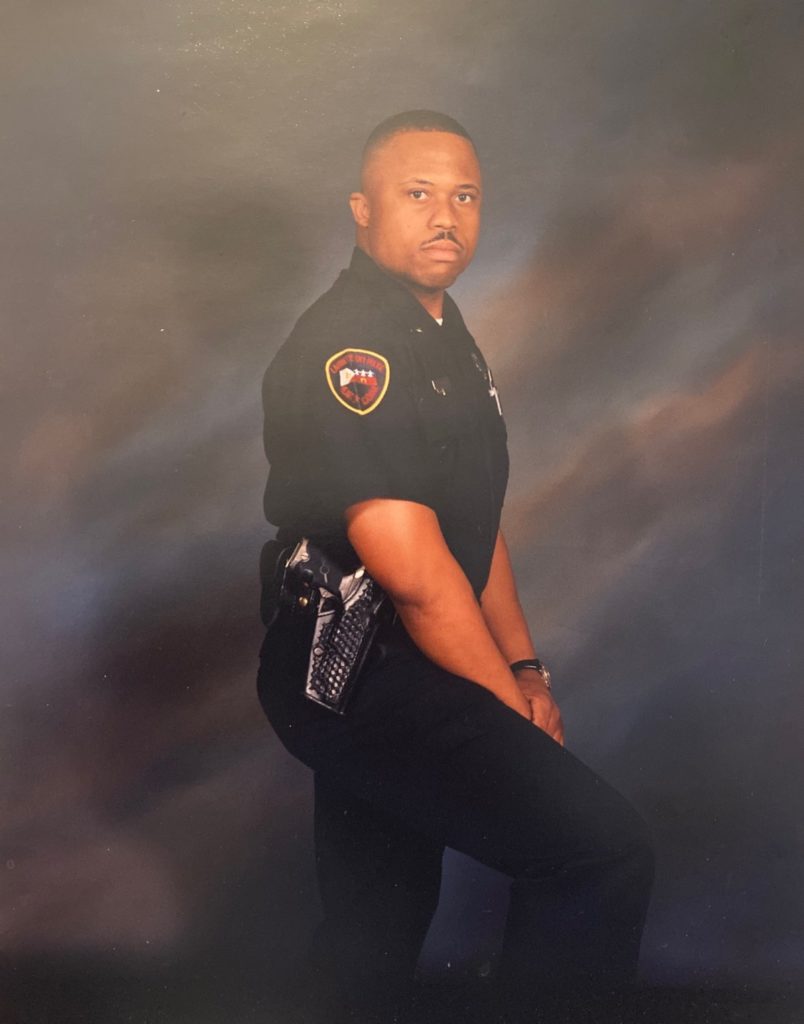

Reggie Thomas, a thirty-year veteran of the Lafayette City Police Department who recently retired, shares his journey of growing up in the Ninth Ward of New Orleans, joining the police force in 1990, and how an effective police department works to build trust in the entire community in this edition of Discover Lafayette with Jan Swift.

In the aftermath of the George Floyd killing in Minneapolis, public outcry has caused intense scrutiny of the inner workings of police departments nationwide. Retired Deputy Chief Reggie Thomas is in a unique position to comment on the need for change as he has lived on both sides of the issue: growing up as a black teen in the 9th Ward in New Orleans, he was exposed to rampant neighborhood criminal activity.

Reggie was encouraged to escape his neighborhood by a kind mentor, Melvin, who led Reggie to join the Air Force upon graduation from high school. Reggie expressed special gratitude for Melvin, who took him under his wing, as Reggie’s dad had been shot and killed when he was seven.

The traumatic event of his father’s murder shaped Reggie’s beliefs as to how law enforcement should operate as his family never got closure on his dad’s death or learn who may have committed the crime. In fact, the only call ever made to his mother was in the middle of the night informing her of the death, and the promise to follow up with a visit by police never occurred.

Having never left New Orleans, Reggie was amazed at how clean and well-maintained Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio was upon arrival as a new recruit. It opened his eyes as to how the world could be.

After a stint in the Air Force, Reggie returned to New Orleans and worked in corrections with former Orleans Sheriff Charles Foti’s office. He remembers the New Orleans police as being “thugs on the street” at that time. There was no diversity in the ranks and Reggie understood why no one would call to report police harassment as “there was no one to call because nobody cared. No one (in a position of power) took it seriously.”

He shared an example of how he was mistreated right after he had gotten his badge from the Sheriff’s office. Sitting on a porch with a group of his friends, police officers stopped when they spotted the group of young black men. “The police always stopped when they saw a group.” Ordered to put their hands on the police car, Reggie explained that they weren’t doing anything but talking and that he was an officer himself. When he showed his badge to the police officer, the officer kicked it across the street saying, “You’re not a police officer, you’re just a corrections officer.” Sheriff Foti was quite upset at this incident, but it was representative of a larger problem of brutality for no reason.

Reggie moved to Lafayette with his wife, Lisa, in 1990 when she enrolled at USL. Her brother was a recruiting officer for the Lafayette City Police and he convinced Reggie to join the force. He remembers the department as being professional and respectful of its citizens, but the force was not diverse and black officers were lower in rank. Off-color jokes about race were common and he had to look the other way more often than not.

His career started off in narcotics which is dangerous work. And the worst case scenario happened on one occasion when he was returning from inter-department work in Patterson LA on an undercover drug deal. Reggie was still on duty, driving back down the highway in an old car and dressed the part of a drug dealer, admittedly speeding. He was stopped by a state trooper and ordered to “Put your hands on the hood!” While he didn’t have drugs on his person (from the undercover assignment), he did have his gun still strapped to his body. Reggie explains the trauma of the moment, saying “I feared for my life, he was so rough, and I had my gun on me.” The hood was so hot, Reggie pulled his hands back instinctively and was warned close up, in his ear, that he had only one more chance to comply. It was only when his fellow white officers who had been following him back to Lafayette pulled up and explained to the trooper that Reggie was indeed a law enforcement officer that he was released.

Growing up as Reggie has, he understands the need for the citizens to trust its police department. When he assumed the position of Lafayette’s Interim Chief in 2016, the first thing he focused on was solving murder cases. He felt it was unacceptable that so many cases were unsolved and within 90 days, the department had solved five cases. This attention to homicide cases has remained in place and last year, all homicide cases were solved. Reggie’s family history of his own father’s unsolved homicide, in which the New Orleans police never followed up, has shaped his determination to follow up with families. “I understood what it meant for a police officer to follow up. I knew if we could build trust in the community, citizens could become a real part of the police force.”

As Deputy Chief, Reggie instigated Community Walks by the police throughout neighborhoods. He knew that if you could get a leader in each community, and bring them all to the table, you could solve a lot of criminal problems. Neighborhoods such as Mc-Comb Veazey, Fightinville, Freetown, and Truman came together and opened doors to the police as they realized that the officers cared. Reggie explained that you can get information to solve crimes and get drug dealers off the streets once you have the trust of locals.

The Community Walks did more for the police than it did for the community as it gave them a chance to get to know the residents and families and relate to them. Most of an officer’s work is conducted in his car these days, generating reports, and they don’t walk neighborhoods as police did in the past. Reggie would prefer to see police assigned to one area so they can get to know the people.

“Putting more police officers out isn’t the answer,” according to Reggie. And the terms, “zero tolerance” and “more boots on the ground” have been horrible. It causes the community to feel attacked when they get ticketed for minor offenses such as jay-walking, it hurts “the good people” and you destroy the opportunity to build healthy relationships that will encourage people to open up to help solve bigger crimes and make their community safe again.

When asked how he would reform policing, Reggie first emphasized that Lafayette has a great police department. But even given that, changes in the structure of the system would go a long way in enhancing its effectiveness, as well as others throughout the state of Louisiana.

The number one way to reform the police is to have more diversity in the department, to more accurately reflect the population they are policing. Reggie realized great strides in hiring more minority officers when he served as Interim and Deputy Chief, raising the percentage from 11% to 22% in the four year period from 2016 to 2020. With a 35% minority population in Lafayette, there is still a ways to go.

The Lafayette department began actively recruiting minorities at historic black colleges such as Grambling and Southern, and local churches, four years ago. Reggie believes the best police officers come from the local neighborhoods, as they know everyone, went to high school together, and “you want to recruit those guys.”

Unlike many other police departments in the U. S., Louisiana police don’t have unions, they operate under civil service rules. Civil service is “all about seniority” so if one officer has been on the job even one day longer than a more qualified one, the seniority rules when it comes to who gets a promotion. Talent or education are not figured into the decision as to who is moved into leadership positions. It can be a morale killer according to Reggie. So reforming or eliminating civil service is a way to enable the hiring and promotion of the most competent officers.

Another issue brought up is the need to reform Internal Affairs (“IA”) within police departments. Police “police” themselves when there are allegations of excessive force, malfeasance in office, or the killing of civilians while on duty. Reggie believes that experienced civilians can provide unbiased oversight and that the IA should be independent and operate outside of the police force.

When an officer is disciplined, the letter of reprimand remains in an active file for 18 months and is then privately archived with IA. Some officers are repeat offenders over the years, but if a prior event occurred over 18 months prior, it can not be used when determining the proper discipline. The only way that an officer’s commission can be taken away is if he is convicted of a crime, and that needs to be changed, according to Reggie. He commented, as an example, that the officer in the George Floyd case had eighteen prior complaints of excessive violence, yet there he was on the street.

It is possible for police officers to quit a department before being fired and move on to join another city’s force. Smaller towns can’t typically afford the training that goes into commissioning officers and they welcome these cost savings. But this practice also reinforces keeping “bad apples” on the street and Reggie commented that he knows of some officers who are now employed at their fifth police department as they’ve moved around due to problematic behavior.

Body cameras were instituted in 2016 in Lafayette; when the sirens and lights go on, or the taser goes on, the camera is activated. Cameras give the department a first hand seat as to what happens and can help in training. Reggie believes that Lafayette is one of the top departments in the country insofar as training, equipment and personnel are concerned.

People are speaking of defunding the police, and Reggie shared his ideas of how to more effectively utilize trained professionals who may be better suited for some types of enforcement needs in the community. The police are routinely called when there is no criminal activity involved, from kids playing basketball in the street, to the next-door neighbor being too loud, to picking up mentally ill people on the street. Reggie recommends funding professionals for dealing with the mentally ill, as an example, as police aren’t trained in that area and when they show up in their uniforms it can scare the person and the situation can escalate out of control when the mentally ill person begins to fight and the taser comes out. In many communities, police departments engage civilians to show up at car accidents and non-criminal activities to help the individuals involved and keep the police out of the scenario.

Not everyone is a criminal or a thug; some are mentally challenged. If the officers can get to know people, they will be able to address the situation and shut it down before things escalate out of control. Reggie stressed the need to have a reliable partner to pull each other off if things do escalate. According to Reggie, one of the officers in the George Floyd situation had only been on the police force for two days, but he was just as culpable because he stood by and watched without taking appropriate action. Reggie stated he would have arrested Officer Derek Chauvin on the day of the event and then gone into the community to speak about what happened. But the unions prevent that course of action, mandating a “waiting period,” and that is what makes people so angry when they don’t see justice carried out. Any other individual who had committed this atrocious act would have been arrested on the spot.

This interview is an insightful look into a life dedicated to public safety for all of our citizens. Thank you Reggie Thomas for your service to our community.

For a similar podcast broadcast recently on Fresh Air, which looks into the statistics and reasons for much needed police reform, visit https://www.npr.org/podcasts/381444908/fresh-air