Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 52:07 — 71.6MB)

On this episode of Discover Lafayette, we welcome Charles Boustany, a retired cardiovascular surgeon who served as the U.S. Representative for Louisiana’s Third Congressional District from 2005 to 2017. Most recently, he earned a Master’s degree in history from the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. Dr. Boustany was honored with the Richard G. Neiheisel (Phi Beta Kappa) Graduate Award, recognizing the graduate student with the highest academic accomplishment in a classical arts and sciences degree.

Dr. Boustany reflects on a life that has bridged medicine, public service, and now scholarship, and what lifelong learning means at every stage.

Growing Up in Lafayette — Medicine and Mentorship

“I grew up here in Lafayette and went to the old Cathedral Carmel, which was 1st through 12th grade,” he shares, recalling his early education before attending USL (now UL Lafayette) for pre-med studies. Following in his father’s footsteps, he completed medical school and surgical training at Charity Hospital in New Orleans, an experience he describes as legendary in its rigor and reputation.

A formative influence on his life and career was Dr. John Ochsner. “John taught me not only the techniques and things you learn as a heart surgeon. He taught me how to be a surgeon, how to be a doctor. He was an amazing individual and a lifelong friend.”

After additional cardiovascular surgery training in Rochester, New York, Dr. Boustany returned home, practicing for 14 years before an unexpected health challenge changed his trajectory.

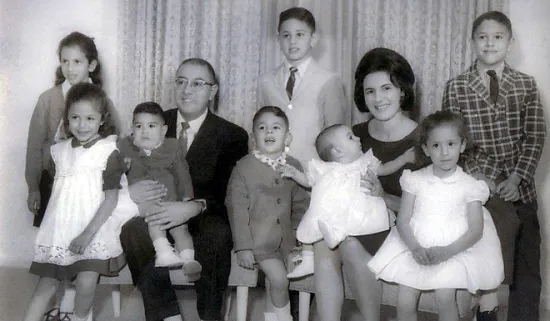

Dr. Boustany speaks with pride about his family’s immigrant story and how it shaped his view of opportunity, responsibility, and community.

“For me, the oldest of ten kids, a doctor, a mom who believed in community service… thinking about the fact that my grandparents all came from Lebanon. They had nothing. They came to this country and the opportunities were there if you took advantage of them.”

He describes that journey as something bigger than one person’s career: “It’s just one of many great American stories.” He ties his family’s arrival and the immigrant fabric of Lafayette to what makes the community distinct: “That’s what makes Lafayette so unique for a city its size. It’s got a very diverse population, and it has a population that has an international outlook, which creates all kinds of opportunities.”

And he adds a personal glimpse into the household that raised ten children: “My mother had a lot of energy and she kept us all in line, amazingly.”

A Turning Point — Health Care and Public Service

At age 48, after developing severe cervical spine issues that forced him to retire from surgery, Dr. Boustany faced a crossroads. That moment coincided with a deeply personal family health crisis in 2001:

“This was a very distinctive point in time for me. I was at the peak of my career in my surgical practice. But 2001 was this horrible year for me, my wife and our kids. Both kids had different life threatening conditions that cost a ton of money out of pocket over and beyond what insurance could pay. It was a huge, huge struggle. Navigating the health care system is a disaster. It was hard for me. I wondered, “What are people doing? How are they managing this?”

The experience stayed with him. As he watched national debates over health care and foreign policy unfold, he felt called to act. “Honey, I gotta make a difference,” he told his wife Bridget one early morning before announcing his decision to run for Congress.

In Congress — Katrina, Rita, and “Rita Amnesia”

Dr. Boustany’s first year in Congress was defined by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. While national attention centered on New Orleans, much of Southwest Louisiana was devastated by Rita.

“I had to get all of it amended to include Rita. And that’s when I coined the term ‘Rita Amnesia.’”

He recalls warning a national reporter: “My fear is that we’re going to have Rita amnesia.” The phrase stuck and became part of the legislative fight to ensure Southwest Louisiana was not forgotten.

He also recounts a pivotal moment after Katrina, when First Lady Laura Bush spent the day touring Lafayette with him. “I was told initially she’s going to be on the ground for about 45 minutes. So I arranged to take her to the Cajun Dome and then Acadian Ambulances’ communication center to see what was going on. Well, she ended up spending the whole day with me. When I took her back to the airport, she thanked me and said, what else do you need? I said, I need 15 minutes on the phone with your husband. Sure enough, Sunday morning at 6 a.m., my cell phone rings and it’s President Bush. He called me Doc. You know, he had nicknames for everybody. He said, Doc, I heard Laura had a good trip down there. What’s going on? What do you need? I said, bottom line is the state doesn’t have the capacity to deal with the magnitude of what we have. We need federal assets down here to help out in New Orleans. He said, ‘I’ll talk to the staff. You get the delegation to Baton Rouge at 9:00 tomorrow morning. Monday. The governor is going to be there. I’m coming in with my team, and we’re going to have a powwow, and we’re going to talk about this and organize it.’ And that’s when everything changed. That’s when he brought in General Honore.”

That conversation helped catalyze greater federal coordination and response.

Reflecting on those chaotic days, he credits his surgical training: “My career as a surgeon dealing with really dire, immediate emergencies, I just sort of methodically figured out, okay, this is what I can do. This is what I’m going to do. And I didn’t panic.”

How a Surgeon Approaches Congress

Dr. Boustany explains how medicine shaped his legislative style: “As a surgeon, I had to deal with people from all walks of life. It could be a grandmother or the CEO of a prominent company. It could be a farmer, or somebody who has no insurance and is poor. I had to learn to be able to communicate with the full spectrum of humanity. I think that gave me an advantage, as a doctor, but also as a surgeon, because I had to gain the trust of these people. You know, I’m going to operate on your heart, stop your heart and do all this stuff. So, being able to present yourself in a way and communicate with people from all walks of life, different levels of education and earn their trust was a big asset for me when I traveled the district and tried to find support. That training, that background was very helpful.”

He approached Congress with humility, seeking advice from senior members in both parties. One piece of counsel stood out: “One of the most prominent ones was don’t be a know it all. Pick a few subjects and learn everything there is about it. Once you start to speak about these things, people will quickly see that you know what you’re talking about and then they’ll respect you. But if you go down there and spout off on every issue, people see through that pretty quickly.”

He developed expertise in health care, foreign policy, energy policy, and international trade, areas that later informed his graduate studies in European history and international affairs.

Returning to the Classroom

After leaving Congress and later retiring from consulting, Dr. Boustany found himself restless. A seminar course at UL Lafayette rekindled a lifelong passion for history.

“The more I’m thinking about this, I really love this history stuff. I don’t want to just be a consumer of history. I don’t want to just read about it. I want to maybe I can contribute to the field.”

His master’s research took him to Columbia University’s Rare Books and Manuscripts division, where he spent a week combing through primary source documents to complete his thesis.

Receiving the Neiheisel Award was especially meaningful: “It was thrilling for me when I finished this master’s program to get the Richard Neuheisel Award, because my very first semester at USL in 1974, I took a world Civilization class with him, and I was told he’s a really hard, demanding teacher. And other students, when they asked me what I had signed up for and I told them, they said, you need to drop that class. He’s a really tough professor. You don’t want to take it with him. And I said, oh, that’s the kind of guy I want to take it with. And I did. And you know, I got an A in his class and he and I subsequently became friends. I’d go sit and talk in his office. We’d just talk about history.”

Dr. Boustany has now been accepted into the PhD program in history at Louisiana State University, where he plans to study modern European history beginning in 1500 — research that will require time in European archives.

Health Care Philosophy — “Information, Choice and Control”

When asked what still matters in health policy, Dr. Boustany reduces it to six words.

“Information, choice and control.”

“People want clear information about their health condition and their options… They want that to be between them and the doctor.”

And equally important:

“Affordability, accountability and quality.”

“Quality is critically important. If you put quality first, I think the cost will come in line.”

Lifelong Learning and Adaptability

Dr. Boustany closes with a reflection that defines this next chapter: “It’s like I always tell students: Chance favors the prepared mind. One of the keys in getting older and being able to deal with challenges in life is adaptability and education, and preparing your mind, to be able to pivot.”

From the operating room to the halls of Congress to the archives of Columbia, and now toward a PhD, Dr. Charles Boustany’s journey is a testament to resilience, intellectual curiosity, and a lifelong commitment to service.

He is even considering expanding his master’s thesis into a book, and perhaps, one day, a memoir.

For Lafayette, it is another reminder that some of the most compelling American stories begin right here at home.